Private road transport has consistently dominated the modal split in most metropolitan areas around the world. Factors such as greater convenience, independence, flexibility, comfort, speed, and, reliability, combined with the historical investment in road infrastructure, have contributed to increasing the modal share of private vehicles over public transport. This trend persists despite recent government efforts to encourage the use of mass transit alternatives, which generally have not prevented light vehicles from remaining the most convenient alternative for commuters.

The overextended growth of traffic in cities has led to a troubling increase in congestion, pollution (air and noise) as well as other negative impacts such as safety and social inclusion concerns. As these adverse effects are accentuated by the increasing concentration of population in urban areas and the urgent demands of global warming, public administrations are increasingly launching initiatives in favor of public transport together with sustainable transport strategies (e.g., promoting cycling, recovering urban spaces for pedestrians, etc.).

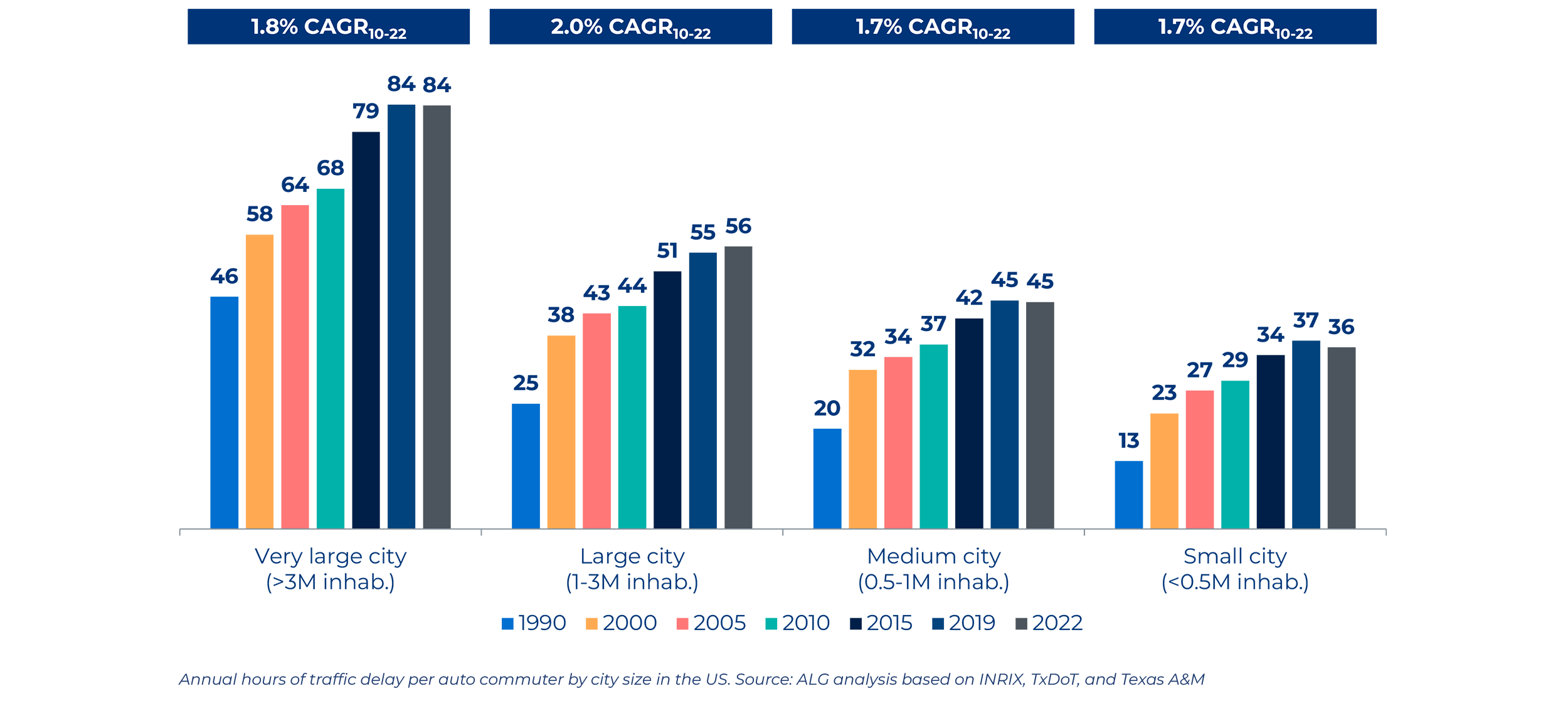

Statistics on traffic delays by city size in the U.S. reveal an upward trend over the last 30 years. The effects of the pandemic (telework, e-commerce...) have not managed to reverse this tendency, as congestion levels from 2019 were already restored by 2022. In addition, the analysis by population volume indicates that this upward trend, as well as congestion levels, increase with city size.

Considering the anticipated growth in population density within major urban centers, it is reasonable to assume that congestion-related issues will continue to worsen in the future, as these large cities already experience the highest congestion rates.

The increasing use of electric cars will help mitigate some of the negative impacts of road transport, mainly GHC emissions, but will not solve the structural issues arising from increased traffic in the city, such as congestion, safety, capacity restrictions, urban pacification, social equality, etc.

The potential of public transport-friendly initiatives to encourage the modal-shift

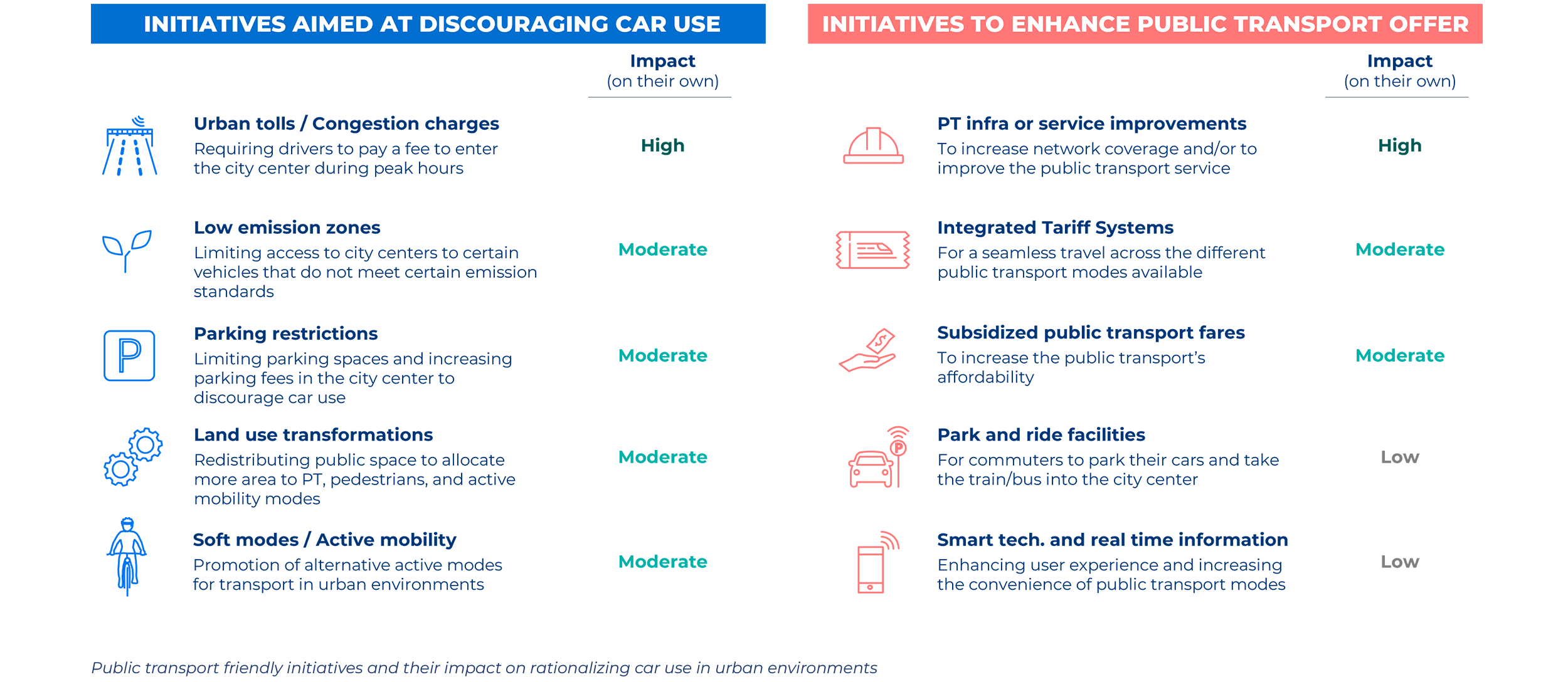

There are numerous examples of pro-public transport policies recently implemented to address the need to adapt quickly to a changing environment and reduce transport-related emissions. Ultimately, these initiatives aim to rationalize private car use in favor of public transport alternatives and other soft modes. These measures can be classified based on whether they aim to discourage the use of private vehicles (directly or indirectly) or to enhance the public transport offer.

In order to maximize their effectiveness, cities often implement multiple initiatives in parallel, thus enhancing and complementing each other’s benefits. For instance, the impact of park & ride facilities on alleviating traffic congestion is typically modest on its own. However, when combined with reduced public transport fares or enhancements to the transportation network, its impact can become substantial.

However, in general, these strategies have yielded few results compared to the effort invested: while public transport and soft modes have increased in European and U.S. cities, car use continues to grow overall at a higher pace.

Impact of fare reductions on public transportation

With the pandemic, some governments and policy makers reduced public transport fares, allowing us to assess the impact of these initiatives on the modal split in urban environments. In this section we will analyze some examples of these initiatives, focusing on their impact on public transport ridership and the overall modal share.

Spain provides a good example of this. The government offered free suburban train services to frequent users, plus an additional subsidy equivalent to discounts of up to 50-60% on metro passes in most Spanish cities. This initiative has been maintained from September 2022 until the end of 2024, with the ultimate goal of reducing the use of private vehicles and Spain’s carbon footprint. In the 2023, this measure endowed about 2,000 million euros (combining both initiatives on suburban trains and metro passes), illustrating the magnitude of the policy and investment effort.

However, the poor accessibility and low level of service of commuter trains, resulted in a limited success for the public transport sector, well below expectations. The initiative was also weakened by not including in the discount the fares of other modes of public transport (bus lines, trams, etc.). Based on available data in the Madrid metropolitan area, subsidizing public transport, even with a high effort, was not enough by itself to reduce significantly the number of cars in the city.

Furthermore, several mobility studies conducted by the UITP in some European cities showed that a reduction in fares did not always translate into a direct increase in the modal share of public transport for commuting at the expense of private vehicles. For instance, in 2020, the local government in Lyon, France commissioned a simulation study to explore the potential of implementing full free fare public transport (FFPT) as a strategy to reduce congestion, lower transport GHG emissions, and free up public space. The study concluded that while implementing FFPT within the TCL network could result in a ridership increase of 15-30%, most new trips would stem from current cyclists and pedestrians rather than car users.

Another initiative in Hasselt (Belgium) implemented a full FFPT system in 1997 to alleviate congestion around the city center, opting against constructing a new ring road. Prior to FFPT, the existing bus network, consisting of eight buses and four lines, was largely underutilized. The initiative was paired with an expansion of services, increasing the number of bus lines from three to nine and enhancing frequency, along with restrictive measures to limit car traffic and reduce parking. As a result, bus ridership surged by 700% following the introduction of the FFPT scheme. However, 63% of the new trips were made by existing bus users, while 21% were attributed to cyclists and pedestrians, and about 16% were from former car users. Although the FFPT system was discontinued in 2014, the operator managed to retain a significant portion of travelers, with 75% of weekday riders and 67% of weekend riders still using the service, The decline in ridership primarily occurred on short-distance routes that attracted pedestrians. This suggests that public transport usage has become ingrained in mobility behavior, driven by the combined strategies of FFPT, bus service improvements, and car use restrictions.

Finally, Tallinn declared mass transit modes (buses, trains, and trams) free for residents in 2013. Ten years after the implementation of this initiative, commuters have been steadily choosing cars over mass transport modes. The Estonian government reported that PT use in Tallinn has fallen from over 40% in 2013 to less than 30% in 2022, while commuters who drove to work rose from 40% to 50%. The insufficient coverage of the public transport network and the affordability of the private vehicle have allowed the car to remain the most attractive alternative in the city. On the other hand, combining two bus routes into a faster and more frequent line resulted in a 70% increase in ridership, showcasing that improving the service attracted more car users than the free PT measure.

These experiences suggest that an increase in public transport fare subsidies by itself has a very limited impact, and it requires a competitive offer in terms of service and network coverage in order to encourage modal shift. This means that complementary strategies must be put in place, not only in terms of public transport supply (cost, travel time reliability, comfort, safety, network coverage, etc.), but also through initiatives seeking to rationalize car use, stressing the need for a comprehensive approach to policymaking.

The following section evaluates the impact of the new integrated ticketing system (“Navegante”) implemented in Lisbon’s Metropolitan Area in 2019 in more detail. The new system led to a substantial fare reduction as well as an improvement in network coverage and service quality by integrating the different modes of public transport into a single card. This provides us with a valuable example to evaluate the impact on modal split derived from a reduction in public transport fares together with an improvement in its level of service.

Case Study: Measuring the impact of the “Navegante” Integrated Tariff System (ITS) in Lisbon

In April 2019, the “Navegante” ITS pass became operational in Lisbon, allowing for the use of all public transport operators with free transfers (bus, train, metro, ferry, and bicycles) throughout the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (AML). The new ITS also led to a significant reduction in the price of public transport, with two different monthly passes offered at €30 and €40/month (depending on the range of municipalities included), as well as an improvement in network coverage (from 30% to 100% of AML’s territory covered by the intermodal pass).

In the year following the launch of “Navegante”, the number of passes loaded in Lisbon increased by 20%, from less than 7M in 2018 to around 8M in 2019. The preferred mode of transport among ITS users was by far the bus (55% of the demand in 2019), followed by the metro, train, and ferry. After mobility restrictions were relaxed in the wake of Covid-19, figures indicate a continued upward trend, as the Navegante pass usage exceeded 9M in 2023. This represents a 42% growth in PT ridership compared to 2018, before the new ITS pass.

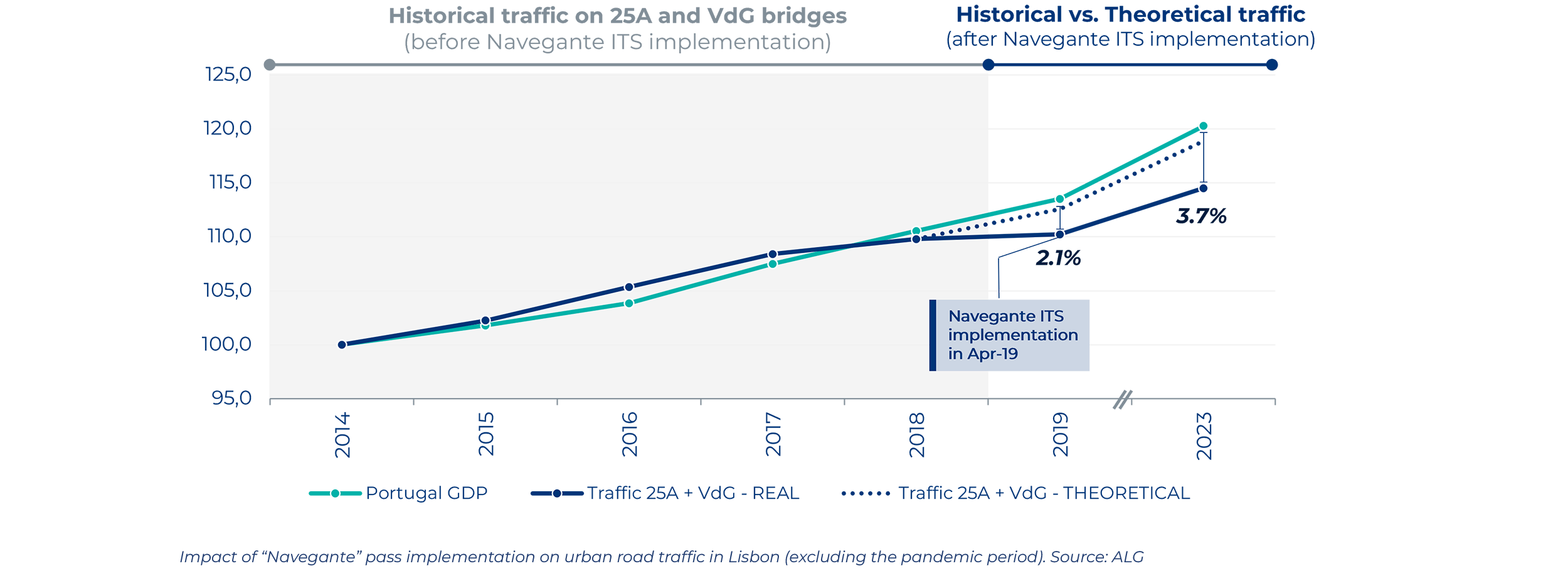

If we analyze the motorized traffic through the two access bridges to the city (April 25th and Vasco de Gama), we can conclude that the integrated ticketing system and its associated fare reduction had an impact on the modal split for access to Lisbon. Taking into account the historical behavior of traffic prior to the implementation of the “Navegante” Pass in 2019, we observe that urban traffic on the two bridges grew less than what could be expected organically considering the economic growth of the country. While traffic historically showed an elasticity of 0.94 to Portugal's GDP after the economic recession (2015-2018; excluding the rebound effect), the implied elasticity for 2019 was 0.15. This initiative also continued to impact motorized traffic after the pandemic, showing an implied elasticity far from the historical trend (0.50 in 2023 vs. 0.94 historically).

Thus, we can estimate that the implementation of the integrated ticketing system combined with the service improvements in public transport in Lisbon resulted in a reduction of motorized traffic of 2.1% in 2019 and 3.7% in 2023, compared to the theoretical figures. In terms of users, this means a saving of more than 8,300 vehicles/day on the two access bridges to the city from the Setubal peninsula, which now prefer the public transport alternative after the implementation of the new ITS pass.

Conclusions

Municipalities and policymakers face a major challenge due to increasing levels of road traffic, leading to higher levels of congestion, GHG emissions, safety issues, and other adverse effects.

As a result, there are increasing new initiatives in favor of public transport to rationalize the use of private vehicles in major cities worldwide. The international scene offers a good benchmark of this, with new initiatives that extend beyond traditional subsidies or infrastructure investments: ITS, congestion charging, low-emission zones, park & ride facilities, etc.

Experience shows that initiatives focused exclusively on reducing public transport fares (as we have seen in Spain, Estonia, and other cities around the world) typically have a reduced impact on increasing its share in urban mobility and reducing the number of private vehicles, typically below expectations.

On the other hand, the reduction of fares, combined with the improvement of public transport services, offers greater success, as seen in Lisbon’s case, with the introduction of a new ITS pass (“Navegante”) in 2019.

It is therefore imperative to develop a holistic mobility solution for the citizens rather than relying solely on fare reductions, to enhance the overall passenger experience.